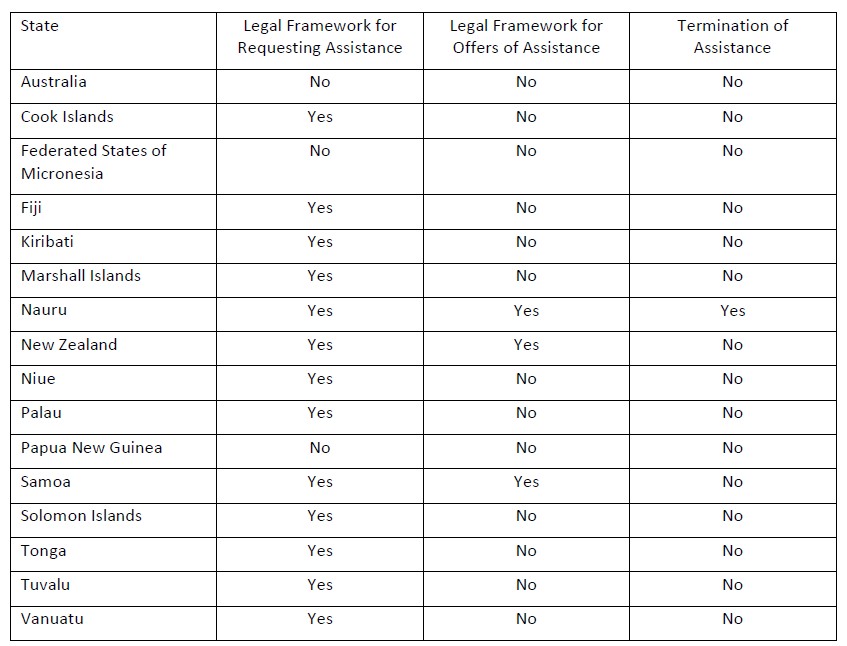

The following provides a basis for an assessment of Pacific wide approaches to legal preparedness for international disaster assistance (based on the IDRL Guidelines). The regional analysis examines overall similarities and differences between states in the Pacific, before providing a regional snapshot” of trends and challenges against the IDRL Checklist areas. The analysis concludes by exploring the possibility of developing a regional approach to such issues as a method to enhance coordination, cooperation and resilience in the context of natural disasters.

Disaster Management Legal Frameworks

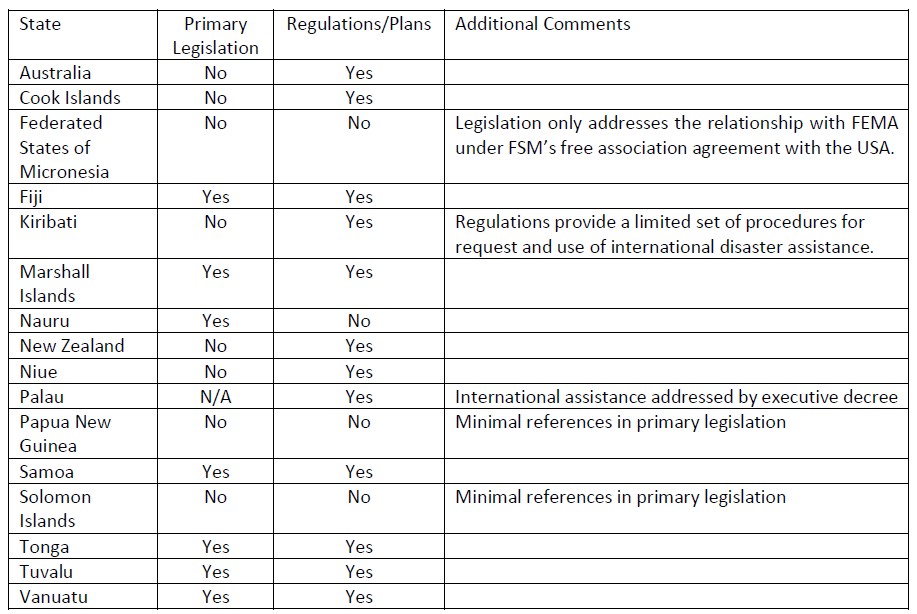

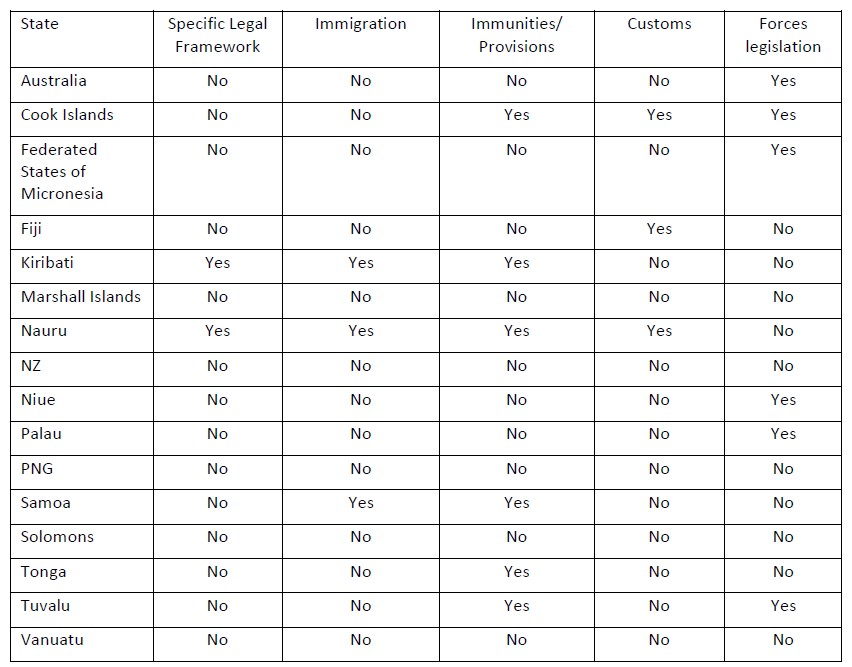

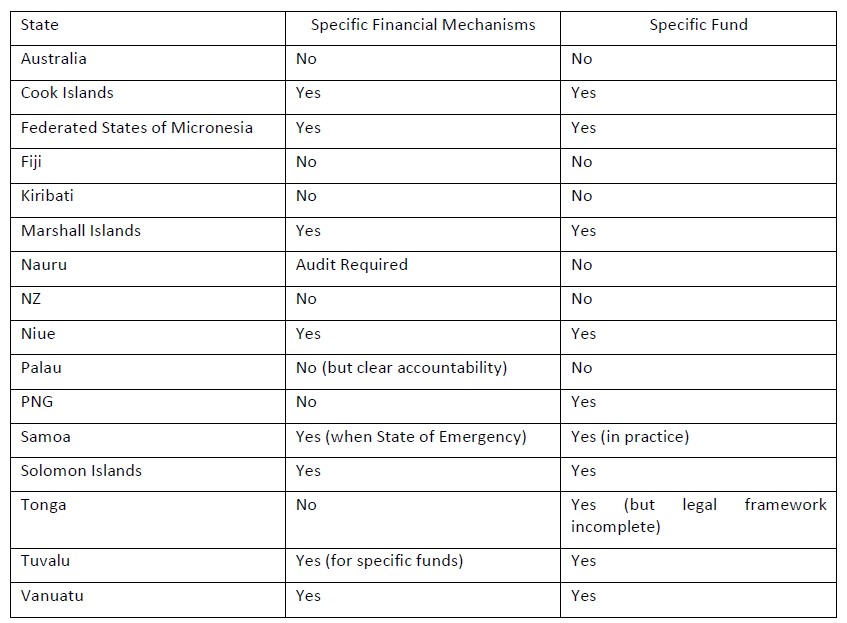

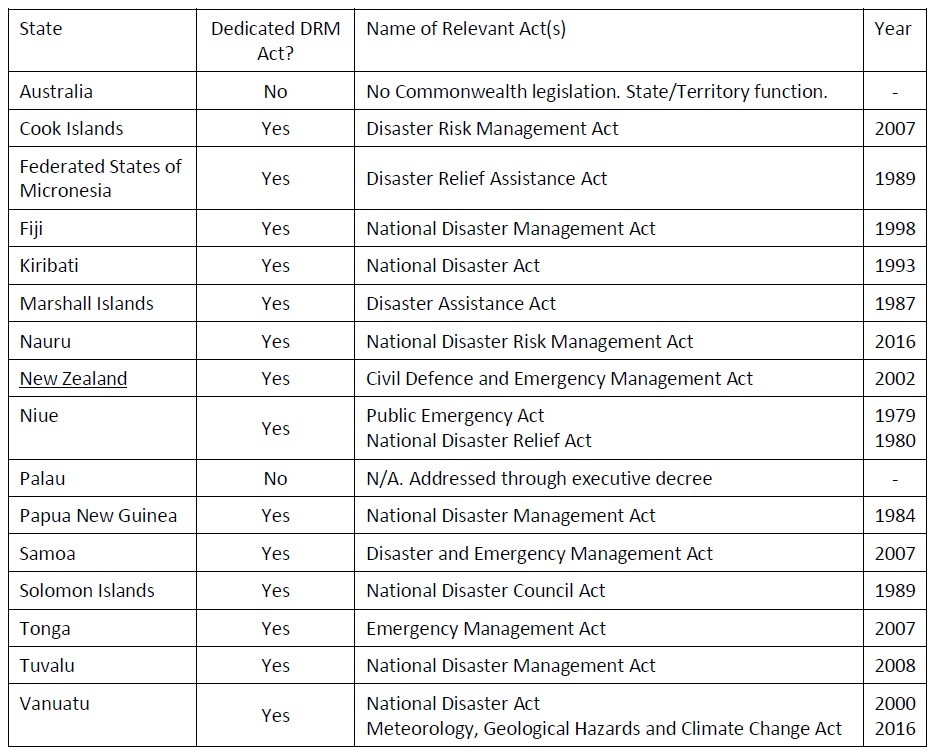

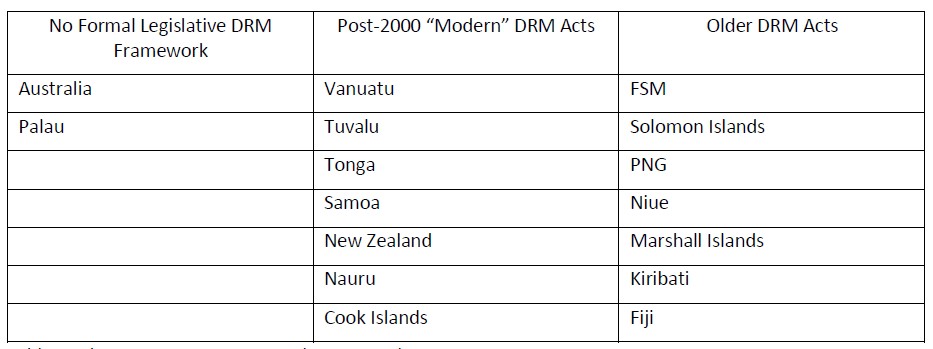

Although the table above confirms the existence of a legislative disaster law framework across all but two of the states concerned, this is somewhat misleading. In fact, the content of these frameworks varies dramatically. These can be divided into three broad groups, namely those without a formal legal framework at all, those with more modern (post-2000) frameworks and those based upon older disaster or emergency acts which tend to pre-date the development of global principles around IRDL. These are summarised in table 2 below:

Older examples, as might be expected, have little or no reference to international assistance as they pre-date the principles of IDRL by several years (several decades in some cases). However, even more recent examples do not, necessarily, follow the IDRL guidelines, given that only two were promulgated in the post-IDRL era (Tuvalu and Nauru). Nevertheless, the development of IDRL as a concept can be detected in many of the elements within these later acts. The end result of this is a wide range of approaches across the Pacific towards disaster law generally and international assistance in particular.

In all cases, significant elements of the legal framework are found in secondary legislation, planning documents (the legal status of which vary) and informal/soft law practices and documents. This creates practical difficulties. In most of the states examined, secondary legislation is often all but impossible to access outside the states concerned (with Fiji, Australia and New Zealand being the primary exceptions). This issue is particularly problematic when legal issues which are central to international assistance are often found outside the disaster law framework, in general acts dealing with business as usual issues. This leads to a legal map that is both complex (being found across several legislative acts) and difficult to access.

The lack of a primary legislative framework around IDRL, while not fatal for the operation of IDRL within the states concerned, does provide a barrier for effective understanding among outside agencies who lack the guidance that an easy to access legislative framework can provide. Lacking these signposts, the details of international assistance and co-operation can be difficult to locate.

In all of the states examined, many of the details around international assistance law are to be found in planning documents that co-exist with the formal legal framework. This compounds the above issue as these documents are often detailed, dense and complex making them difficult to understand, particularly to those outside the state concerned. This is made more difficult by many of these documents not being available online.

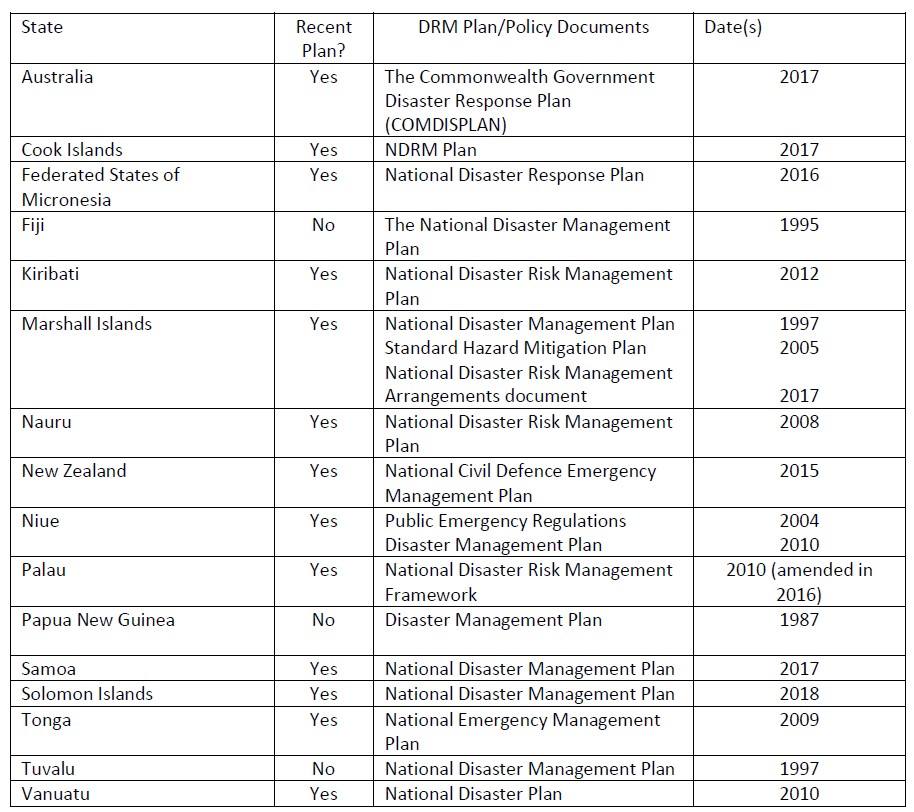

The exact nature of these plans varies dramatically, as does their status within the system. In many cases, the response planning document is part of a wider DRR plan, with has a quasiformal status, but this is not always the case.

Three examples utilise plans which appear to be outdated (Fiji, PNG and Tuvalu). In the cases of PNG and Fiji in particular, references to organisations and practices found in the plans do not appear to accord with the situation on the ground and at times appear to contradict the legislation. In general, the age of the planning documents reflects the extent to which they address international assistance specifically or in any detail. As will be seen from the following sections, the later plans tend to address such matters more explicitly

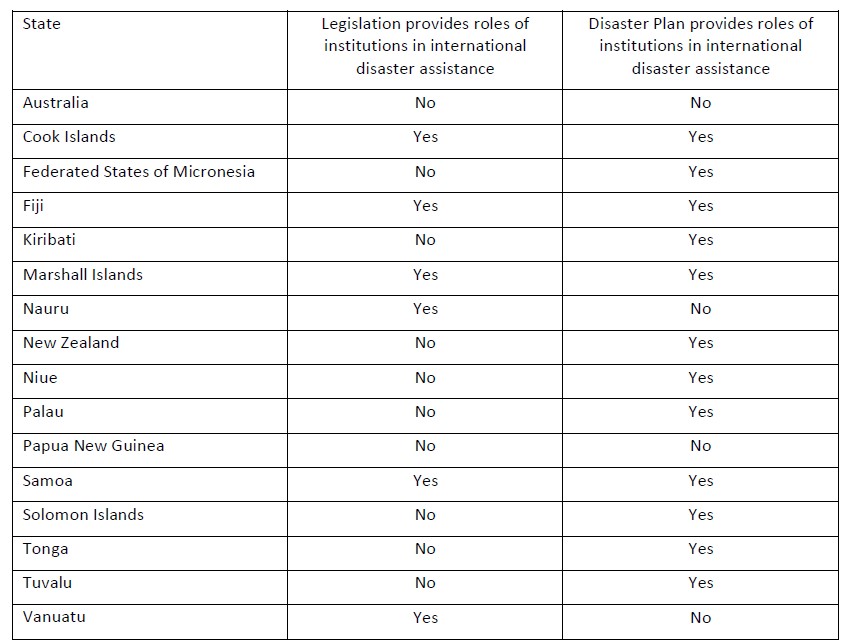

The plans themselves are often required under primary legislation but their exact legal status can be unclear. However, in practice, many states seem to regard them as formal law rather than informal or non-legal guidance documents. Whatever the exact legal status of these documents (they might perhaps be best seen as “deemed regulations” in the New Zealand context) functionally, they should be regarded as part of the legal framework and this is the approach taken by the research team.

However, including specific procedures and processes around international assistance (and other aspects of response) within planning documents can be problematic. These documents are not written with the precision of law but rather in the language of policy. In some cases the researchers found it hard to find the exact elements of the plan relating to international assistance and in some examples the processes were vague or confusing in their specifics. The situation is made further complex by elements within some plans being contradictory and difficult for the outsider to understand.

While a domestic NDMO or government may be well aware of how the process will work, for those unfamiliar with the specific legal context of the state concerned the details can be confusing. Given that trained lawyers, familiar with the field and Pacific legal systems, undertook this research, it is suggested that, in a response situation some international assistance actors may struggle to undertake the processes required and thus risk delays and confusion in the delivery and management of response assistance.

Overall Assessment – IDRL in the Pacific Region

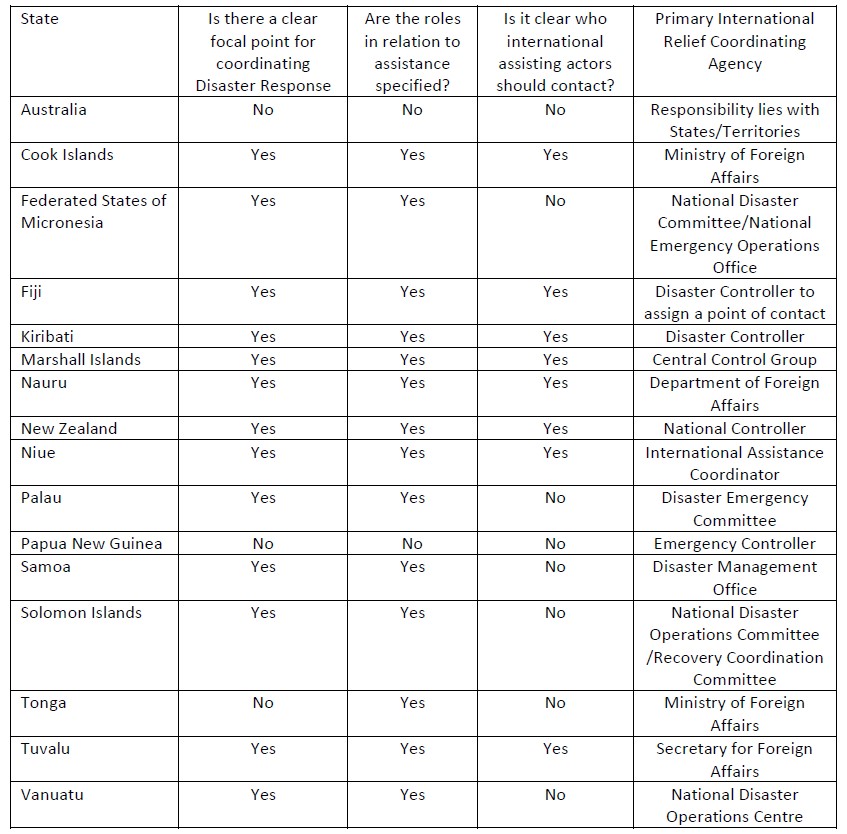

The approach of the 16 Pacific Forum states examined towards International Disaster Response Law can be broadly divided into three categories. The majority of states have some form of formal legislative framework around disaster management (the exceptions are Palau and, to some extent, Australia) but amongst the majority there are significant differences. One group exhibits significant alignment with the IRDL guidelines, although the mechanisms by which these are achieved still vary. These examples have been enacted in the last decade (i.e. alongside the development of the IDRL guidelines themselves) and are a reflection of IFRC encouragement, assistance and support in the development of these legislative frameworks.

The second group have legislative frameworks that predate the IDRL. This latter group can be further divided into two sub-groups. Firstly, there are a number which, although having a legislative framework that might be regarded as “outdated”, have planning documents that do provide some clear guidelines around the management of international assistance. However, much of this is not legislated for or is to be found in a variety of sources. The second subgroup have a limited legislative frame and minimal formal guidance around the provision of international assistance.

However, these broad categories can create a misleading impression. Although a number of states do provide legal frameworks that do appear to comply with the IDRL guidelines and (the Pacific draft guidelines), a deeper analysis reveals a slightly different picture. In many cases there remains significant reliance upon discretionary actions by executive (often political) actors and a significant lack of certainty around the detailed operation of many of the elements of IDRL which are outlined in the legislative frameworks or planning documents. This is particularly problematic given the difficulty in sourcing legal and policy documents in many Pacific Island jurisdictions.

The researchers are well aware of the particular challenges that face desktop legal studies of Pacific legal systems and this area of study is no different. These include a lack of online materials and central repositories of Pacific legal documents. In recent years, this situation has been made worse by resourcing issues around PACLII (the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute). In addition, informal or soft-law documents (plans, guidelines, codes of practice, etc) can be exceeding difficult to source from Pacific island states.

![]()