The following provides a basis for an assessment of Pacific wide approaches to legal preparedness for international disaster assistance (based on the IDRL Guidelines). The regional analysis examines overall similarities and differences between states in the Pacific, before providing a regional snapshot” of trends and challenges against the IDRL Checklist areas. The analysis concludes by exploring the possibility of developing a regional approach to such issues as a method to enhance coordination, cooperation and resilience in the context of natural disasters.

Disaster Management Legal Frameworks

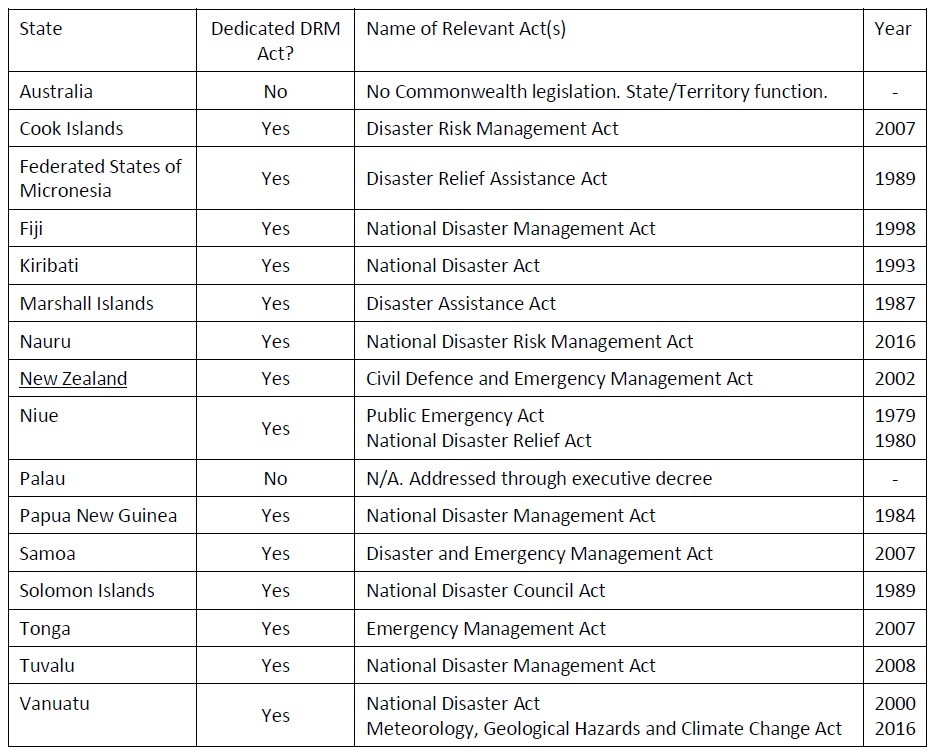

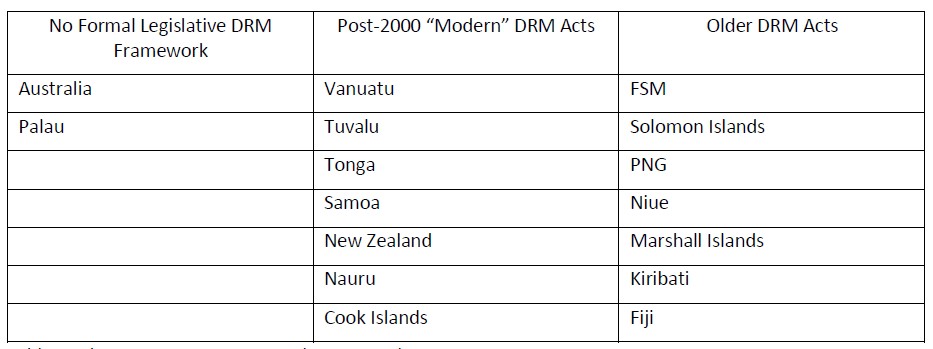

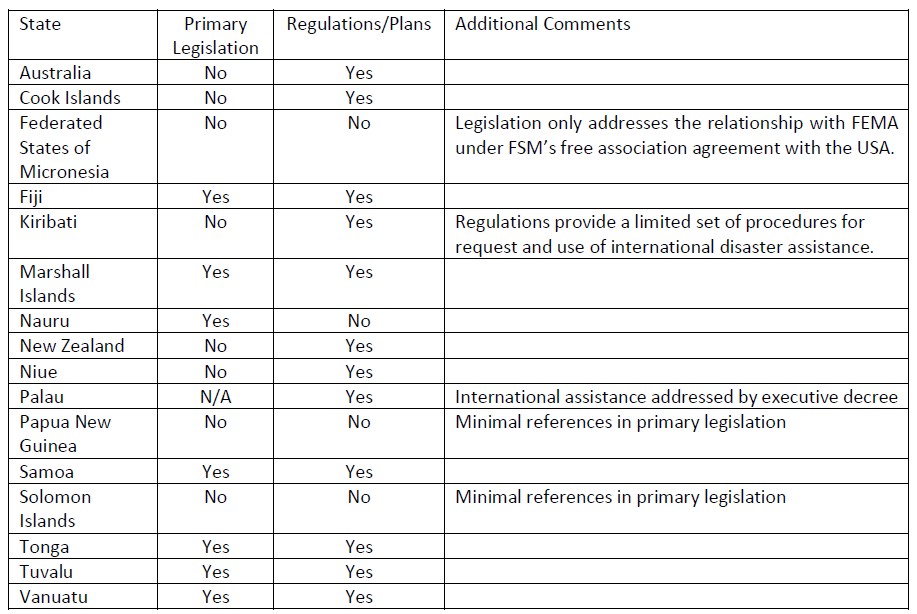

Although the table above confirms the existence of a legislative disaster law framework across all but two of the states concerned, this is somewhat misleading. In fact, the content of these frameworks varies dramatically. These can be divided into three broad groups, namely those without a formal legal framework at all, those with more modern (post-2000) frameworks and those based upon older disaster or emergency acts which tend to pre-date the development of global principles around IRDL. These are summarised in table 2 below:

Older examples, as might be expected, have little or no reference to international assistance as they pre-date the principles of IDRL by several years (several decades in some cases). However, even more recent examples do not, necessarily, follow the IDRL guidelines, given that only two were promulgated in the post-IDRL era (Tuvalu and Nauru). Nevertheless, the development of IDRL as a concept can be detected in many of the elements within these later acts. The end result of this is a wide range of approaches across the Pacific towards disaster law generally and international assistance in particular.

In all cases, significant elements of the legal framework are found in secondary legislation, planning documents (the legal status of which vary) and informal/soft law practices and documents. This creates practical difficulties. In most of the states examined, secondary legislation is often all but impossible to access outside the states concerned (with Fiji, Australia and New Zealand being the primary exceptions). This issue is particularly problematic when legal issues which are central to international assistance are often found outside the disaster law framework, in general acts dealing with business as usual issues. This leads to a legal map that is both complex (being found across several legislative acts) and difficult to access.

The lack of a primary legislative framework around IDRL, while not fatal for the operation of IDRL within the states concerned, does provide a barrier for effective understanding among outside agencies who lack the guidance that an easy to access legislative framework can provide. Lacking these signposts, the details of international assistance and co-operation can be difficult to locate.

In all of the states examined, many of the details around international assistance law are to be found in planning documents that co-exist with the formal legal framework. This compounds the above issue as these documents are often detailed, dense and complex making them difficult to understand, particularly to those outside the state concerned. This is made more difficult by many of these documents not being available online.

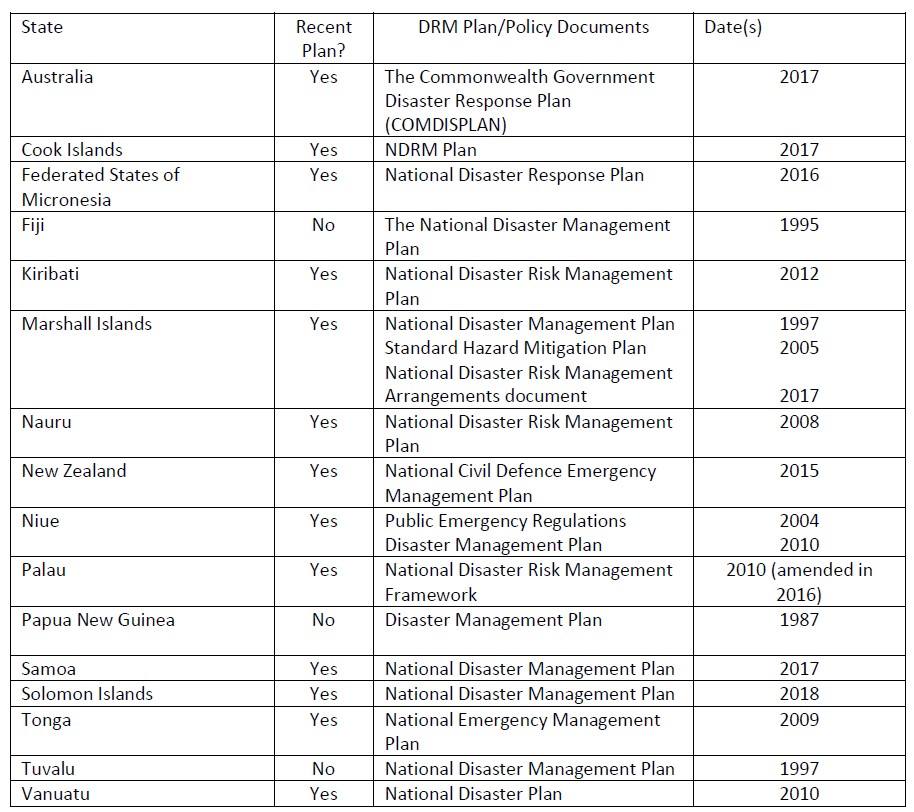

The exact nature of these plans varies dramatically, as does their status within the system. In many cases, the response planning document is part of a wider DRR plan, with has a quasiformal status, but this is not always the case.

Three examples utilise plans which appear to be outdated (Fiji, PNG and Tuvalu). In the cases of PNG and Fiji in particular, references to organisations and practices found in the plans do not appear to accord with the situation on the ground and at times appear to contradict the legislation. In general, the age of the planning documents reflects the extent to which they address international assistance specifically or in any detail. As will be seen from the following sections, the later plans tend to address such matters more explicitly

The plans themselves are often required under primary legislation but their exact legal status can be unclear. However, in practice, many states seem to regard them as formal law rather than informal or non-legal guidance documents. Whatever the exact legal status of these documents (they might perhaps be best seen as “deemed regulations” in the New Zealand context) functionally, they should be regarded as part of the legal framework and this is the approach taken by the research team.

However, including specific procedures and processes around international assistance (and other aspects of response) within planning documents can be problematic. These documents are not written with the precision of law but rather in the language of policy. In some cases the researchers found it hard to find the exact elements of the plan relating to international assistance and in some examples the processes were vague or confusing in their specifics. The situation is made further complex by elements within some plans being contradictory and difficult for the outsider to understand.

While a domestic NDMO or government may be well aware of how the process will work, for those unfamiliar with the specific legal context of the state concerned the details can be confusing. Given that trained lawyers, familiar with the field and Pacific legal systems, undertook this research, it is suggested that, in a response situation some international assistance actors may struggle to undertake the processes required and thus risk delays and confusion in the delivery and management of response assistance.

Although most states surveyed provide a legal framework to address international assistance, the exact nature of the provisions and their nature vary dramatically. Most states provide some primary legislation on the subject but in a minority of cases these issues are entirely dealt with in secondary regulations or planning documents. This difference of approach creates some complications with the clarity of the procedures but even amongst similar legal approaches, the substantive differences are dramatic.

In the case of Nauru, for example, the provisions for international assistance are clear and framed by the disaster legislation. This provides a well-defined system, whereby the President is authorised to make such requests upon the advice of the Disaster Council and the Cabinet. In such circumstances, the request must be accompanied by a list of the required assistance plus information on the procedures by which such assistance must be provided. The clear and comprehensive nature of the Nauruan act can be contrasted with the treatment of international assistance in Papua New Guinea where, although international assistance is covered by the legislation, very few details are provided.

Most states fall somewhere between these extremes. Fiji, for example, provides a clear if limited set of procedures around requests for international assistance and is notable for the specific barring of unsolicited aid unless approved by the National Controller. Another point of note is the approach of Niue which, although providing a very limited legal framework, does provide for the (Ministerial) post of International Assistance Co-ordinator to act upon Cabinet decisions to request assistance. In almost all cases where the process is defined in the legal framework, the final decision lies with the political branch (usually in the form of the cabinet). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (or equivalent) takes the formal responsibility of handling the request in cases where this is set out in law or policy.

A degree of variability amongst states as regards systems for the requesting of international assistance is understandable given the difference in governance and constitutional structures. However, it is debateable whether the current level of variance is optimal or necessary. It is clear that a number of states do not currently comply with the IDRL guidelines and the risk of confusion and poorly coordinated aid exists in a number of jurisdictions. At the very least, many Pacific states would benefit from clearer set guidelines around structures for requesting assistance and consideration should be given to regional coordination of such requests.

Elements of the current systems (both formal and informal) are explored in more detail in the sections below.

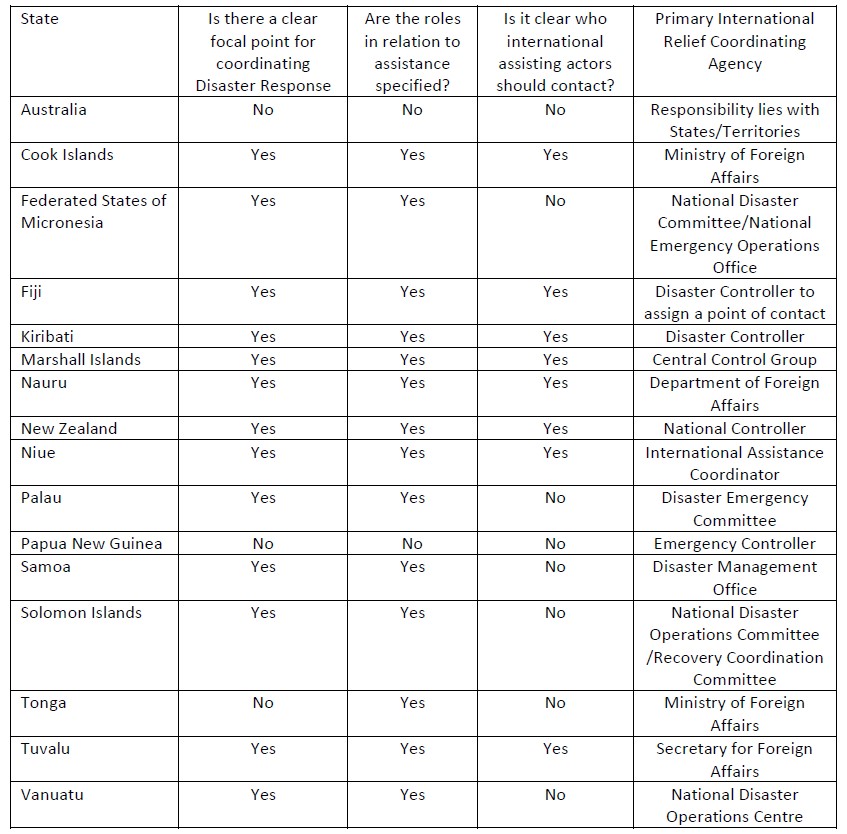

The ability of states to interact with international assisting actors is crucial to delivery of effective assistance in a timely manner. It is therefore somewhat concerning that there is a lack of clarity around a single point of contact in many of the states studied as can be seen from table 5. In a number of cases there is no clear and obvious coordination point for international assisting actors to contact (although the authors accept that this may exist).

In many cases the exact role of the NDMOs and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is unclear. In Tuvalu and Vanuatu, for example, the framework names both the Secretary for Foreign Affairs and the NDMO as responsible. In other cases, the point of contact is a committee rather than a specific individual, although further research would be needed to investigate how these models work in practice. The Marshall Islands are also notable for the explicit bar that it places upon direct contact between domestic actors and international assisting states and agencies.

A number of states formally provide a political leader as the point of contact in the relevant legislation (the President, in the case of the FSM), although in practice the policy documentation makes clear that the responsibility lies with a committee (the National Disaster Committee in the case of FSM). In some cases, such as Fiji (under the 2010 SOPs), recent soft law documents have clarified the contact point for international assistance, however, in some cases, even more recent legislative frameworks have failed to create a clear point of contact to those undertaking the domestic response activity.

Overall, the complexity that many Pacific States exhibit in this field seems unnecessary and less than optimal. While it is accepted that the specifics of the national constitutional or administrative position in many states may require a degree of internal complexity, this should be kept to a minimum for international assisting actors. There are some existing examples of this. It is questioned in particular whether the extensive role for the Foreign Affairs Ministries is required outside of providing assistance in relaying the requests.

In the New Zealand model, although it is internally complex, the contact point for international assistance is relatively clear (with the National Controller playing the key role – once again in coordination with MFAT). Nauru takes this a stage further by simply establishing one agency as the key point of contact (Niue also takes this approach by appointing an International Assistance Coordinator).

However, one other element that raises a degree of concern is that when specific agencies or individuals are tasked with the coordination of international assistance, it is not entirely clear that they have the powers necessary to manage such assistance, which may require actions by a number of other agencies (as explored below). In the Cook Islands the recently introduced (2017) Disaster Management Plan provides for a cluster system to provide this role, it is unclear what authority the cluster has to provide the assistance required as the legislation itself seems to be silent on these issues.

Overall, the current situation could be clarified, with each state providing a clear and easily recognisable point of contact within the disaster relief framework. It would also benefit the states concerned if, subject to the constitutional and governmental limits, that the contact point is in a position to ensure that the correct assistance is provided and smoothly delivered. The existence of a regional contact point, as developed in South East Asia to provide a degree of regional coordination is therefore worth exploring.

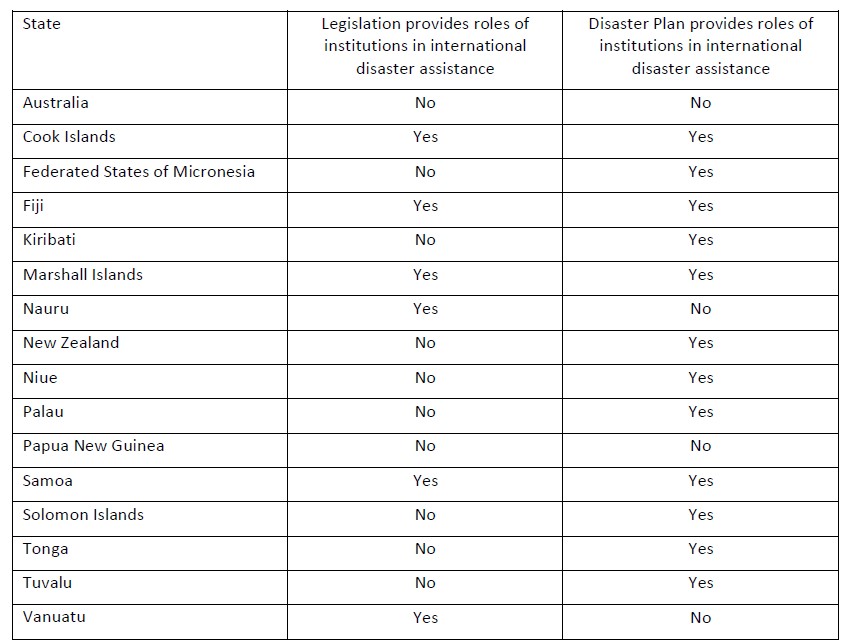

With the exception of Australia and Papua New Guinea, all the states studied provide clear legislative and regulatory guidance around the roles and responsibilities of institutions around international assistance. In Australia’s case the lack of clarity is rooted in the federal nature of the Australian governance model, where states and territories will take the lead in disaster response. In the case of Papua New Guinea, in addition to the devolved nature of the state, the Disaster Management Act (and the Disaster Plan) are silent on the issue with the National Disaster Centre (NDC) merely being recognised as having “all powers” in relation to disaster assistance, which one assumes includes matters relating to international assistance. It is not clear the precise role of the National Emergency Committee in this regard and how it relates to the NDC.

In a number of other examples, the frameworks are set out in disaster management documents. In Palau for example a loose framework exists, while New Zealand has a relatively detailed model set out in the National Civil Defence Emergency Plan. However, although the remaining states largely provide a legal framework, often complemented by planning documents, the details of these arrangements vary significantly. Some provide relatively clear frameworks, such as Niue, where the Emergency Executive Group provides a management or coordination role, cabinet provides requests, customs provides clearance and the police handles security.

In many cases there is a significant and undefined role for the political executive through a National Disaster Committee or some such to provide strategic direction (sometimes working through a Disaster Council of Chief Executives). In one case (RMI), the Chief Secretary is even designated as the Disaster Controller. In these cases, the NDMOs are relegated to support roles. In addition, it is not entirely clear where the role of the NDMO or equivalent fits with these coordinating committees. It is suggested that the unclear role of political leadership in the management of response, and specifically international assistance, is not best practice and risks creating confusion between the roles of the various institutions responsible for coordinating international relief.

The roles and responsibilities of international assisting agencies are only mentioned explicitly in a minority of cases. Nauru, for example, makes specific reference to international assistance having to follow international and regional mechanisms, but this is unusual. More commonly, several states specifically mention international assisting agencies or states in their planning documents. For example, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Tonga specifically make reference to the Red Cross in their planning documents while Vanuatu specifically provides for bi-lateral relationships with France, Australia, NZ and the Melanesian Spearhead Group.

When it comes to providing a clear set of domestic legal frameworks around the coordination of international assistance (and the relationship between the state and such international assistance), it is exceeding difficult to identify a single form of Pacific practice. Instead there is a propensity for frameworks to create rather vague and unclear frameworks around delivery and management which in many cases provide for significant involvement for political committees and high-level civil servants rather than NDMOs. Only New Zealand appears to obviously buck this trend.

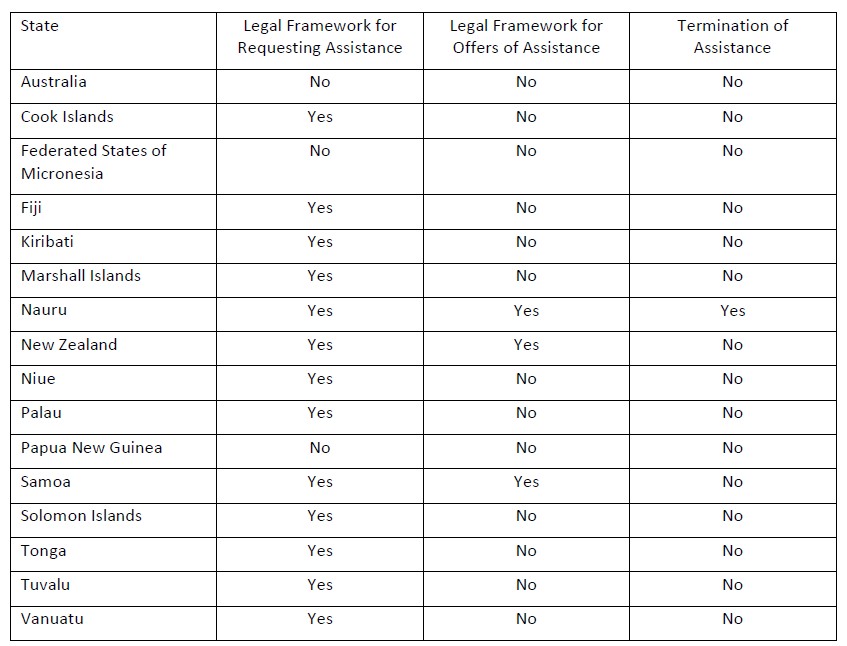

In general, Pacific states all have some form of formal process for requesting assistance (as seen in table 7), although the legal basis for this varies considerably. Only Australia, PNG, Solomons and FSM seem to lack a process at all (or have one that is extremely vague). However, others such as Palau operate a framework for such requests, which lacks formal legal status. In most cases, the decision lies at the political level with the national controller or equivalent providing advice only, in some cases via an officials committee. Only New Zealand puts this power primarily with the National Controller, who must take their assessment to Cabinet to be actioned by MFAT. However, the existence of a legal (or quasilegal) framework in the field does not in itself mean that the process is clear or detailed. As already discussed above, a number of states operate systems which are not particularly clear and, in many cases, are to be found in policy documents that are not easily available to outside actors. When the process sits in a planning document, there is also the issue that it need not be followed within the state concerned.

While the existence of a formal framework for requesting assistance exists in most cases (although the details vary), few states operate a formal mechanism to deal with unsolicited offers of assistance. Nauru and New Zealand are notable exceptions, with Fiji also having an explicit bar upon such unsolicited donations. While other states recognise the issue (particularly Vanuatu), the powers to explicitly address the problem of unwanted or inappropriate offers of assistance, through a formal process, do no currently exist in most states.

The same is true of mechanisms to end international assistance, with only Nauru having a formal explicit process for ending the period of international assistance. The current practice appears highly discretionary and does not provide certainty for international assisting actors and domestic response or recovery agencies.

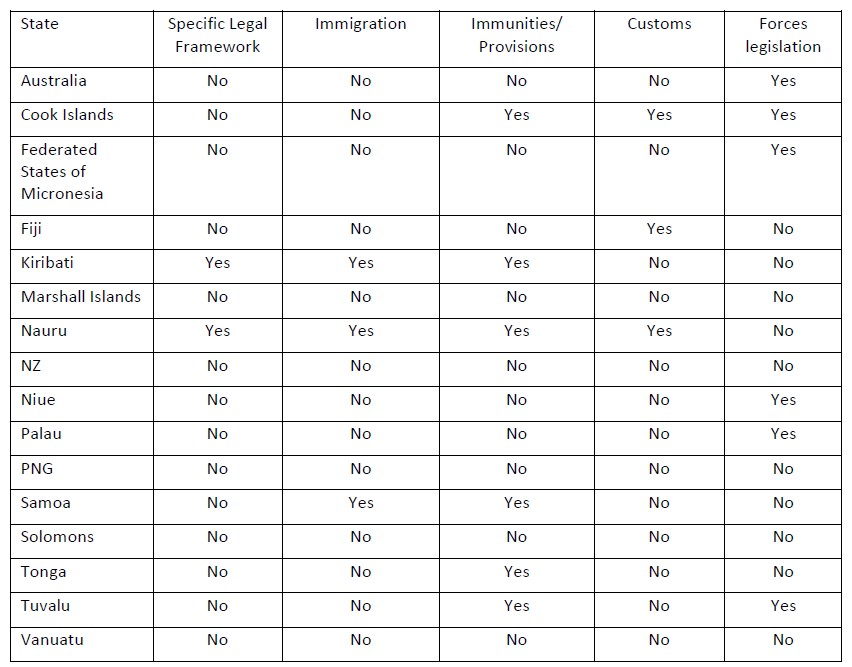

Specific legal frameworks in regards to incoming assistance actors, goods and equipment vary across the jurisdictions examined. As can be seen from table 8, very few Pacific Forum states have developed a single legislative framework around legal facilities for incoming assistance. Obviously, this is not to say that the states concerned do not have processes in place to manage these issues, but they are generally disparate and spread across a number of legislative frameworks. This approach treats disaster events as a general exception to business as usual in fields such as immigration and customs (as well as other aspects of the legal system). In some cases (but not all) these are signposted in the relevant plans. This makes research in the area difficult, as to locate where specific legislative elements applicable to international disaster assistance are found requires a survey of the whole legal system. For this reason, it is likely that the summary provided in this section and in the national reports is incomplete.

However, this difficulty is relevant to the research as a whole, as the lack of a single framework makes the legal situation unclear to international assisting actors. This is compounded in those cases where the possibility of providing legal immunities and processes exists but is within the discretion of a Minister or Official. In these cases, which are often general discretionary provisions (unconnected to the specific needs of international disaster assistance), the assisting actor is still left with a lack of clarity as to the process, its timeliness, the requirements needed and the extent of the exception/immunity likely to be granted. In a few cases they are entirely ad hoc. For this reason, the information included in table 8 only includes specific legislative frameworks and not those aspects included in plans and actioned through discretionary actions. These subtleties are explored in a little more detail below.

A discretionary approach with assisting actors and goods being provided with specific visa or customs exemptions as part of a wider discretionary scheme (or schemes) appears to have been then Pacific norm until recently. There is a clear trend towards a more specific disasterrelated model but only a small minority has, as yet, taken the decision to incorporate these elements into a specific disaster law framework (Nauru and Kiribati). In a number of other states, there has been a degree of consolidation through disaster planning documents (e.g. Cook Islands, Fiji), which provide guidelines around specific exceptions and processes for disaster assistance. However, it is not clear that the legislative framework provides the capacity to deliver the aims set out in the plan.

More commonly, the disaster plan provides only vague assistance and the frameworks remain rather un-coordinated with individual custom, immigration and other legal immunities and privileges spread across the national legal framework.

The overall picture is thus one of a complex and unhelpful legal framework for international actors which, except in some specific examples (armed forces and named international organisations), have little certainty around their legal status within the countries concerned, as well as the processes for entry and providing assistance. This leaves the international assisting entity at risk from legal uncertainty, which could limit their activities or leave them exposed to unintentional legal jeopardy. The 2016 Samoan IRDL review concluded that Samoa would benefit from greater consolidation and clarity around legal facilities in relation to international disaster assistance. This conclusion could be applied to most Forum states and the approach taken in Nauru perhaps offers a model pan-Pacific approach.

Amongst the Pacific Forum states studied, only Nauru provides a clear reference to quality standards in its disaster legislation and Customs Act. The few specific quality standards that do apply to international assistance in the Pacific Island states are applied almost exclusively through this latter means. In a number of states (including Australia, New Zealand, Tonga and Vanuatu), although the standard licensing requirements of medical practitioners and other response professionals apply, there is the possibility of an exemption. However, these exemptions are not specific to disaster response.

A number of states place responsibilities within their planning documents for assisting agents to comply with the requirements of the plan (or develop specific SOPs, as in FSM) and act under the instructions of the national coordinating bodies. These statements seem somewhat vague and the documents themselves do not appear to have the force of formal law. It is therefore questionable the extent to which they can be enforced.

Overall, the lack of a standards framework for international assisting actors appears to be a significant gap in the law and risks unqualified actors providing assistance or qualified ones operating without authorisation. Coherence around quality frameworks for the provision of assisting actors, goods and equipment appears as a legal gap in almost all Pacific Forum states and the establishment of a Pacific-wide standards framework thus seems a logical step to avoid duplication across the various jurisdictions.

With the exception of Nauru, there are no formal eligibility requirements around assisting actors in any of the states studied. In the Nauru case, these facilities are applicable only during the international disaster relief and initial recovery periods. These will be granted to intergovernmental organisations and states (and any other organisation deemed appropriate) directly by the Secretary of the National Emergency Service. A formal application process exists for those outside these categories.

In a number of Pacific states (Vanuatu and Kiribati), offences exist against those who obstruct disaster workers in their duties. This category is defined as those carrying out their responsibilities under the National Disaster Plan, which will include international assisting actors. In addition, some Australian states and Kiribati provide that those working under the disaster plan are provided with immunity for the actions undertaken under the plan. Again, this would apply to international actors, although in Australia the specific nature of the immunity varies according to state/territory in which the disaster occurs.

Given the lack of legal facilities provided to international assisting actors amongst the states examined, it is hardly surprising that eligibility is not something that most states address. However, if legal facilities are to be extended to international actors then this is something that needs to be seriously considered. Again, the approach taken by Nauru offers a model worth applying more broadly, particularly as it includes mechanisms for the removal of such accreditation when the assisting actor breaches its obligations under the disaster plan or legislation. It should also be noted that although some Pacific states do provide (minimal) forms of special legal facilities to international assisting actors the fact that most do not provide clear rules or processes around eligibility (or revocation) should perhaps raise a concern.

The provision of a specialised unit to expedite international disaster assistance is not something that has found favour amongst most Pacific Island Forum states. In the majority of the examples studied, there was no specialised unit of any sort addressing these issues. A few examples have established such a unit in the disaster management plan (e.g. Marshall Islands and Fiji) but this agency (the NEOC and the NDC respectively), although tasked with managing these issues, does not appear particularly empowered to do so. Given that these issues are technical questions of Customs and Immigration, it would seem that these departments are crucial to a successful system. In the Fijian example the Department of Customs and Excise is required to facilitate “… entry of all official disaster assistance commodities and waive customs and excise duties, where appropriate”, however in the RMI no such legislative backing appears to exist.

New Zealand is unusual for establishing an International Assistance Cell (IAC) within MFAT’s international Co-Ordination Centre (ECC), which incorporates Customs Officials. Although, even here, the practical management of international assistance entering into New Zealand is not specifically dealt with.

The lack of a single agency to facilitate international disaster assistance is something that the IDRL report on Tonga (2015) commented upon in relation the Tongan experience. However, the evidence of this study suggests that this is a recommendation that could be applied more widely to the Pacific as a whole.

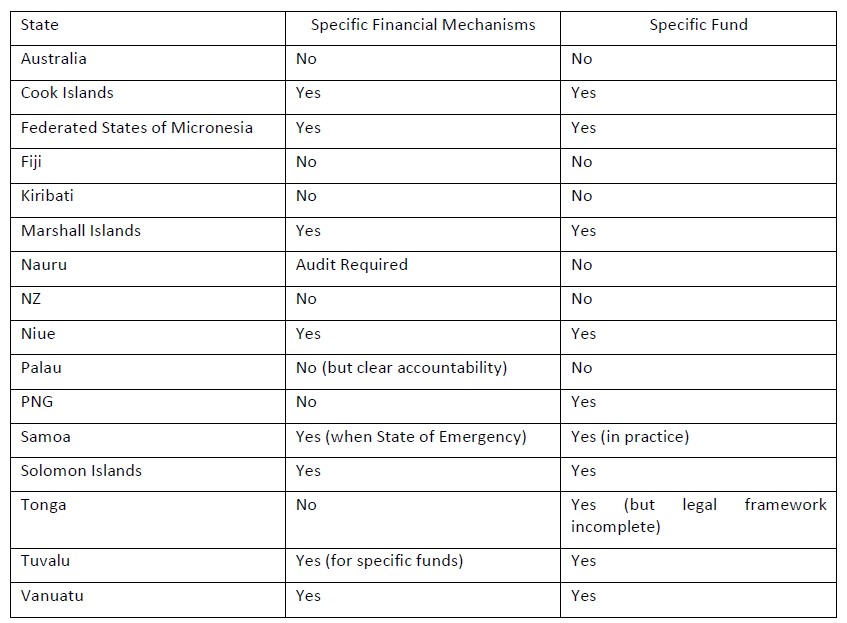

Pacific approaches to the financial accountability of funding vary dramatically. A majority of states (nine of the 16 studied), operate a separate accounting system for external assistance and the establishment of a separate fund for such payments. One (Samoa), though not formally required to established such an entity, does so in practice. However, the exact nature of these funds vary. In the case of Tuvalu, the funds established have a wider range of uses relating to the mitigation and prevention of disasters and climate change. In other cases, such as Niue or Kiribati, the resources of the fund can only be used for the recovery efforts of the specific disaster (including payments to individuals).

The same variability is evident as regards the auditing and accountability of international assistance. The arrival in small island states of large amounts of immediate financial resources or assistance in the form of goods, creates significant problems around fraud and misuse of resources. This is recognised in a number of small island states, where specific auditing requirements apply in disaster situations. In some cases, such as Samoa, these can include “fast-track” procedures, whereby expenditure can be authorised swiftly, while the accountability of the Ministry of Finance remains clear. In others, there are specific requirements around auditing (e.g. Niue) but, in some cases, these appear minimal (e.g. PNG). It is noted that in many cases, post-disaster reviews continue to recognise that effective and swift use of international financial assistance remains a problem in some Pacific states.

Neither Australia nor New Zealand have specific legal frameworks around incoming assistance, although both do address other aspects of international aid. One assumes that this is on the basis that the existing domestic frameworks are robust enough to manage even in the post-disaster situation. However, problems around funding for victims of disasters in both of these states and allegations of misuse of funds, suggests that this may be an assumption that needs re-examined.

The legal status of goods and personnel transiting a Pacific Island state was not something that was clearly defined in most of the states studied. This is an important issue given that in many cases the distances required to provide international assistance to many Pacific states may require elements of the response and recovery effort to be based in neighbouring countries.

Despite this, only one Pacific Island state (Nauru) makes specific reference to outgoing assistance or assistance transiting through the state concerned. The novelty of this act (enacted in 2016) appears to explain the inclusion of this element. However, even in this case reference is relatively minimal, with the Nauru DRM Act merely empowering the government to work with other external actors to facilitate such assistance. Such assistance is to be undertaken utilising the Nauruan law which in this case appears to imply that the specific elements within the DRM Act (and others) which apply to international assistance in Nauru will also apply to such goods and materials emanating from or transiting through Nauruan territory.

Beyond this, there were no specific legal frameworks in place, although Fiji noted that the current review of the National Disaster Management Act would likely include consideration of this issue. In addition, the 2015 Review of Tonga’s approach to IDRL recommended that such legislation be introduced. As yet this has not occurred.

Samoa also confirmed that, although there was nothing in the Samoan legislation to this effect, the provisions of the Samoan NDMP would apply to assistance transiting Samoan territory. It is possible that similar informal arrangements apply in other states although the researchers were not made aware of them.

Both Australia and New Zealand have relatively sophisticated frameworks around the provision of external assistance and both have adopted the Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship. However, neither specifically deals with transhipment (except under generic provisions for the transhipment of goods and equipment).

The lack of consideration of this issue and its potential importance within the region suggests that this another area where regional guidelines or treaty arrangements could be introduced to ensure regional coherence.

Overall Assessment – IDRL in the Pacific Region

The approach of the 16 Pacific Forum states examined towards International Disaster Response Law can be broadly divided into three categories. The majority of states have some form of formal legislative framework around disaster management (the exceptions are Palau and, to some extent, Australia) but amongst the majority there are significant differences. One group exhibits significant alignment with the IRDL guidelines, although the mechanisms by which these are achieved still vary. These examples have been enacted in the last decade (i.e. alongside the development of the IDRL guidelines themselves) and are a reflection of IFRC encouragement, assistance and support in the development of these legislative frameworks.

The second group have legislative frameworks that predate the IDRL. This latter group can be further divided into two sub-groups. Firstly, there are a number which, although having a legislative framework that might be regarded as “outdated”, have planning documents that do provide some clear guidelines around the management of international assistance. However, much of this is not legislated for or is to be found in a variety of sources. The second subgroup have a limited legislative frame and minimal formal guidance around the provision of international assistance.

However, these broad categories can create a misleading impression. Although a number of states do provide legal frameworks that do appear to comply with the IDRL guidelines and (the Pacific draft guidelines), a deeper analysis reveals a slightly different picture. In many cases there remains significant reliance upon discretionary actions by executive (often political) actors and a significant lack of certainty around the detailed operation of many of the elements of IDRL which are outlined in the legislative frameworks or planning documents. This is particularly problematic given the difficulty in sourcing legal and policy documents in many Pacific Island jurisdictions.

The researchers are well aware of the particular challenges that face desktop legal studies of Pacific legal systems and this area of study is no different. These include a lack of online materials and central repositories of Pacific legal documents. In recent years, this situation has been made worse by resourcing issues around PACLII (the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute). In addition, informal or soft-law documents (plans, guidelines, codes of practice, etc) can be exceeding difficult to source from Pacific island states.

![]()